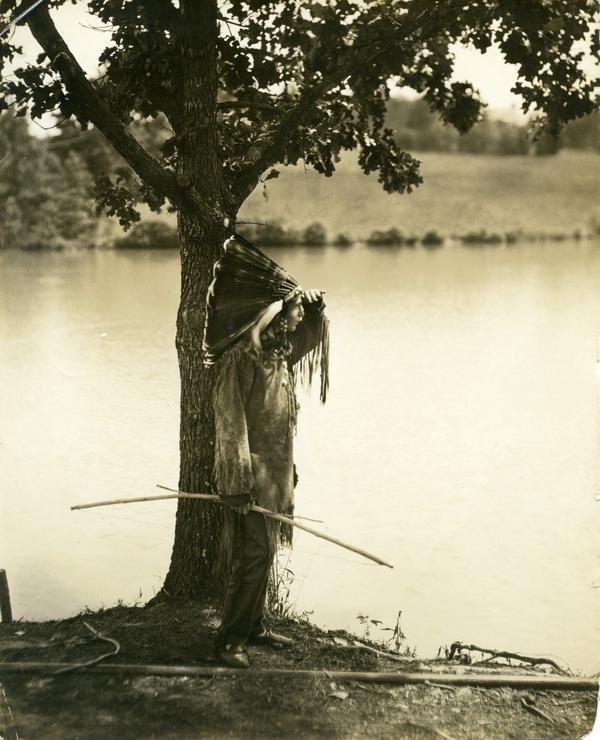

Hiawatha Pageant on Lake Katharine, 1921

By Phil Archer, Deputy Director

By the shores of Gitche Gumee,

By the shining Big-Sea-Water,

Stood the wigwam of Nokomis,

Daughter of the Moon, Nokomis.

Dark behind it rose the forest,

Rose the black and gloomy pine-trees,

Rose the firs with cones upon them…

From The Song of Hiawatha, by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1855)

Cities and private estates throughout the country staged historical pageants during the 1910s, providing visual embodiments of the past. Pageants revised local and national history to suit contemporary nostalgia and civic pride. Today these pageants are ripe for parody (think of the movie Waiting for Guffman and its chipper, clueless pageant about Blaine, Missouri, “Stool Capital of the World”). But in North Carolina the genre has had staying power, with several of the longest-running pageants in the nation continuing to draw enormous audiences, including Horn in the West, Unto These Hills, and The Lost Colony. A century ago progressive-minded people like Katharine Smith Reynolds saw pageants as an educational tool. Children at the Reynolda School learned by performing, and no performance was as ambitious as the Hiawatha pageant staged on and around the sixteen acre Lake Katharine in 1921.

Dramatic versions of Hiawatha had appeared all over the country, from Boston, where it was staged with actual Iroquois tribal members, to San Francisco, where the Reynoldses may have seen it at the 1915 Panama-Pacific World’s Fair. In light of the current exhibition George Catlin’s American Buffalo, it’s notable that many editions of the poem, and the dramatic version that Katharine Reynolds staged, were illustrated with line drawings based on Catlin’s paintings of Plains Indians, even though the Hiawatha legend derives from the eastern shores of the Great Lakes, rather than the Great Plains.

Historical accuracy wasn’t exactly the point. So what did it mean to stage Hiawatha a few years after the U.S. Census Bureau reported that “full-bloods are destined to form a decreasing proportion of the total Indian population and ultimately to disappear altogether?” According to historian Alan Trachtenberg, the Hiawatha pageants helped to transmute the image of the American Indian from “vanishing race” to “first American.” White Anglo-Saxon Protestant educators and writers began to imaginatively reclaim and identify with the continent’s earliest people, assuming for themselves a sense of priority and precedence over new immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe and elsewhere, which they saw as a threat to the “assumed Anglo-Saxon character of the nation.”

The Hiawatha pageant involved a cast of 125, drawn completely from the Reynolda community’s schoolchildren and employees. A professional orchestra performed music inspired by the epic poem, which a drama professor from the University of North Carolina recited from a floating platform anchored in the lake. The cast mingled the children of influential families in Winston-Salem – including the Reynolds, Gray, and Hanes families – with the children of employees, including sons and daughters of the estate’s superintendent, electrician, dairyman, shepherd, and gardener. The role of Minnehaha was given to the elder Reynolds daughter Mary, then fifteen years old. Hiawatha, the young leader who unites warring tribes into the Iroquois Confederacy, was played by Bowman Gray, Jr., future CEO of the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company.

An estimated 5,000 people, seated on the slope from the main house, watched costumed actors performing Hiawatha and Minnehaha’s story on the far side of the lake and in canoes. Professional photographers documented the event, along with a film crew from Universal Pictures, which had grown into the largest film studio in the nation thanks to a hugely successful 1909 film version of Hiawatha. No footage filmed by Universal at Reynolda has yet been discovered. What a discovery that would be, revealing the lake at its fullest and most picturesque. Could it have been the first movie filmed in Winston-Salem?

Reynolda School alumna Tippy Ruffin remembered “We practiced and practiced on the other side of the lake while people stayed on this side to see how much they could see and hear. It went on a long time.”

Elizabeth Lybrook Wyeth, R.J. Reynolds’ niece, recalled “I was one of the chorus, so to speak; they just had to use everybody. I have a picture of us, it’s the most ridiculous thing you ever saw in your life. We were done in sort of gauzy…I suppose it was made out of cheesecloth, and we had daisy wreaths around our heads, and we were the spring breeze or something, I don’t know how we fitted into the pageant. But I can remember that was great fun.” She said that the prettiest girls were selected for the wind phantom dance while others were cast as fireflies and forced to wear black burlap sacks. She claimed that she and Nancy Reynolds (sixth from the left in the above image) were not considered pretty, but because Nancy was “the boss’s daughter,” she got the front row parts.